In the late 20th century, Taiwan was on the brink of developing nuclear weapons, a move that could have significantly altered the balance of power in East Asia. However, a dramatic turn of events unfolded when Colonel Chang Hsien-yi, a senior Taiwanese nuclear engineer, secretly worked as an informant for the CIA. His decision to reveal Taiwan’s covert nuclear program to the United States led to immense political pressure that ultimately forced Taiwan to abandon its nuclear ambitions. While some view Chang as a traitor who weakened Taiwan’s security, others see him as a man who prevented a potentially devastating conflict with China.

Taiwan’s interest in nuclear weapons can be traced back to 1964, when China successfully tested its first atomic bomb. This event deeply unsettled Taiwan’s leadership, as the island remained under constant threat from the communist government in Beijing. At the time, Taiwan was governed by the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT), which had retreated to the island after losing the Chinese Civil War to the communists in 1949. Despite U.S. support, Taiwan feared that, without nuclear weapons, it would be vulnerable to a potential attack from China.

In response, Taiwan’s leadership, under Chiang Kai-shek, launched a secret nuclear weapons program. The project was disguised as a civilian energy initiative and operated under the Chungshan Science Research Institute and the Institute of Nuclear Energy Research (INER). The goal was not to stockpile nuclear weapons immediately but to develop the capability to produce them quickly if needed.

Chang Hsien-yi, a brilliant physicist, played a crucial role in Taiwan’s nuclear project. After earning degrees in physics and nuclear science in Taiwan, he was selected for advanced nuclear training in the United States. During his studies at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee and later at the University of Tennessee, he gained expertise in nuclear engineering—knowledge that would later prove instrumental in both advancing and ultimately dismantling Taiwan’s nuclear efforts.

Chang’s expertise did not go unnoticed by the CIA. As early as 1969, while he was studying in the U.S., he received a cryptic phone call from a supposed company interested in nuclear power. At the time, he was unaware that the call was from the CIA, but years later, he realized they had been monitoring him.

Upon returning to Taiwan in 1977, Chang rose through the ranks, eventually becoming a lieutenant colonel. He spearheaded the development of computer simulations for nuclear explosions at INER, a facility that secretly pushed Taiwan’s nuclear weapons program forward. Despite Taiwan’s insistence that its nuclear research was for peaceful purposes, the United States remained suspicious.

Taiwan’s nuclear program was kept under tight secrecy, but American intelligence agencies suspected that the island was closer to developing a bomb than it admitted. The CIA closely monitored Taiwan’s progress but struggled to find concrete evidence that could force Taiwan’s leadership to halt its plans.

By 1980, the CIA approached Chang again, this time making their intentions clear. They wanted information on Taiwan’s nuclear program, and Chang agreed to cooperate. Over the next several years, he became a key informant, meeting CIA agents at safehouses around Taipei. His handler, identified only as "Mark," debriefed him regularly, asking him to verify intelligence, report on new developments at INER, and even take photographs of sensitive documents.

Chang’s motivations for betraying the nuclear program were not financial—he was not a paid spy. Instead, he was deeply concerned about the consequences of Taiwan’s nuclear ambitions. He believed that if Taiwan successfully developed nuclear weapons, China would launch a preemptive attack, leading to a devastating war. The 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster further reinforced his fears about the dangers of nuclear technology.

As he later explained, he did not see his actions as a betrayal of Taiwan. Instead, he believed he was acting in the best interests of the island’s people by preventing a catastrophic conflict.

By 1988, Chang’s intelligence had provided the United States with undeniable proof that Taiwan was on the verge of producing nuclear weapons. That year, following the death of Taiwan’s President Chiang Ching-kuo, the U.S. saw an opportunity to pressure Taiwan’s new leader, Lee Teng-hui, into compliance.

At the same time, the CIA orchestrated Chang’s escape. He and his family were swiftly exfiltrated to the United States in January 1988. His sudden disappearance shocked Taiwan, and he was immediately declared a wanted person. For years, he remained in exile, unable to return to his homeland.

Following Chang’s defection, the U.S. sent a team of specialists to Taiwan to oversee the dismantling of nuclear facilities. A key plutonium separation plant was shut down, and nuclear materials such as heavy water and irradiated fuel were removed to prevent further weapons development. With Taiwan under heavy American scrutiny, the nuclear program was effectively terminated.

Chang’s actions remain highly controversial in Taiwan. Some argue that he single-handedly deprived Taiwan of a nuclear deterrent that could have protected it from China. Given China’s rapid military expansion, critics believe that if Taiwan had acquired nuclear weapons, it could have deterred Beijing from ever considering an invasion—similar to how nuclear-armed states like North Korea prevent external threats.

On the other hand, some experts believe that a Taiwanese nuclear bomb would have provoked a Chinese attack rather than prevented one. China had warned that if Taiwan pursued nuclear weapons, it would respond with military force. Additionally, the United States, Taiwan’s most important ally, strongly opposed nuclear proliferation and might have distanced itself from Taiwan had it gone through with its plans.

Today, Taiwan relies on advanced conventional weapons and U.S. military support for its defense. Instead of nuclear deterrence, Taiwan has leveraged its dominance in the semiconductor industry, producing about 90% of the world’s most advanced microchips. Some believe this economic leverage—often referred to as Taiwan’s "Silicon Shield"—is a stronger deterrent than nuclear weapons.

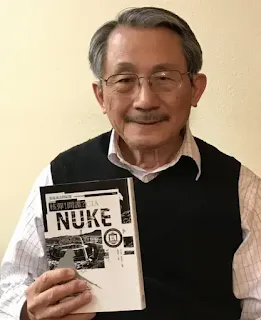

For Chang, now in his eighties and living in the United States, the decision he made decades ago still feels justified. He maintains that he acted with a clear conscience, believing that preventing Taiwan from going nuclear was ultimately the right choice for peace and stability.

Chang Hsien-yi’s story is one of secrecy, moral dilemmas, and high-stakes international diplomacy. His intelligence work for the CIA changed the course of Taiwan’s history, ensuring that the island remained non-nuclear. While the debate over whether Taiwan should have pursued nuclear weapons continues, one thing is certain—Chang’s actions played a crucial role in shaping Taiwan’s security strategy and its relationship with the United States and China. Whether seen as a hero or a traitor, his decision remains one of the most pivotal moments in Taiwan’s modern history.